Museums: Stories beyond silence

In this 21st century, museums have reached far ahead of the previous concepts of ‘ajayabghars’ (house of curios) or just a place to take your children on holidays. Performing the function of cultural hubs, they serve different age groups, intelligences and interests. A place where a young student or a common person may understand how their forefathers used to survive in the absence of modern equipments or what the articles of their amusement were, when there was no TV or internet. Sometimes, a history student can locate something they hadn’t known and a scholar can deduce the psychological behaviours of a particular tribe by seeing their artefacts. Sometimes, the representation of some dying art becomes a special thing to study about past traditions or systems, the physical intentions and social norms woven around it.

Peeping through their showcases, museum artefacts speak a lot without words; about their style, technique, tradition, the period they represent and their journey from their origin uptil the point of reaching the museum. Knowing all these things is like a tour to a dreamland. Passing through different time spans, they uncover various unidentified layers of the times gone by. Though silent, the objects displayed in the museum try to converse with the spectators through their appearance, labels, information panels, drawings and nowadays, audio-visual aids.

Relevance of Kelkar Museum: Architecture and collection

The Raja Dinkar Kelkar Museum of Everyday Art in Pune, Maharashtra, has a pride of place in the historical city of Pune. No tourist visiting Pune leaves without visiting this museum.

Kelkar Museum is located in the Shukrawar Peth; peth being a kind of settlement-cum-market place. Established around Shaniwar Wada, the royal palace of the Peshwas, these settlements were named after days, like Budhwar (Wednesday) Peth, Shaniwar (Saturday) Peth, or the noblemen who took the initiative of setting them up. Surrounded by traditional wadas, a fusion of the Gujarati haveli and Mughal architecture along with the local essence, Kelkar Museum welcomes its visitors with a huge decorative door, locally known as Dindi Darwaja. A number of small, intricately carved windows and an open courtyard at the centre give a feel of a characteristic Marathi atmosphere. These typical architectural features and the medieval collection resemble the cultural face of old Pune.

The huge range of antiquities collected from every corner of the country including domestic objects, textiles, games, sculptures and objects used by famous personalities, bring alive a bygone era. In this way, the museum is a mirror to our past. One of the most characteristic things about it is the vast collection of around 21,000 artefacts, which have been collected by a single person, an optician-poet called Dinkar Gangadhar Kelkar, who started wandering place to place in search of antiques and over a period of 60 years, eventually creating this huge museum. Every piece of this collection is unique in its style, technique, period, artistic and historic values. Seeing these and knowing more about them is a fulfilling activity not only for students and researchers but also for common people.

The beginning

Since childhood, Dinkar Kelkar, alias Kaka, developed a hobby of collecting coins and antique locks. His friends, relatives and neighbours encouraged him by giving him their unwanted old coins and broken, corroded locks. But his collection took shape in a true sense when his family shifted to Pune. Till then, this historic city showed signs of the huge impact the Peshwa reign had made on it. The ancestral mansions (locally known as wadas) of former noblemen and renowned people were full of antiquities like old furniture, weapons, lamps, paintings, jewellery and day-to-day objects.

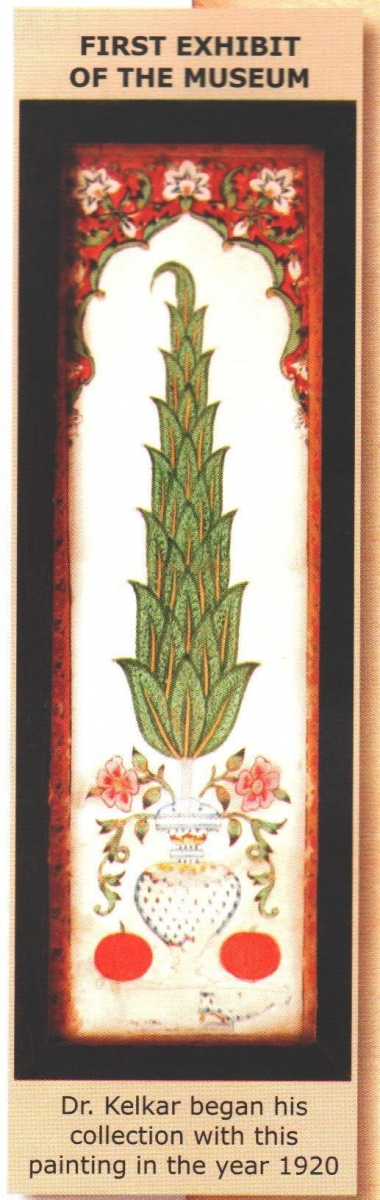

Figure 1

The person who helped initiate Kaka’s collection was Sardar Dikshit-Patwardhan. He was from a very rich and reputed merchant family who were onces bankers to the Peshwas. Once Kaka visited his huge wada and was astonished to see their ancestral objects. Among them, a beautiful painting on the wall grabbed his attention. He asked Dikshit-Patwardhan if he could take it. Dikshit-Patwardhan wondered what he would do with it, for which Kaka also had no definite answer. He just liked it very much and found it to be a collectible. Dikshit-Patwardhan gave him the painting and told him to take any other such items if he wished. This incident set a goal for Kaka Kelkar’s life in 1920. He started visiting old mansions in search of antiques. Often, perceived as being just useless junk by their new-generation owners, he would get such things easily. Also visits to flea-markets of Pune enriched his collection. By doing do, Kaka saved numerous art pieces from destruction and preserved the heritage of society. Today, many of these objects are the only evidences of lost traditions.

Arms and armours

Fig. 2: Sword collection

Raja Dinkar Kelkar Museum has a fine collection of medieval arms and armours. Around 250 in number, these weapons show tremendous variety in style, material and purpose. There are various kinds of swords and hilts; both simple and decorative. Scenes of war and mythological incidents are depicted on some south Indian swords. Here we can also find the famous Maharashtrian gauntlet sword, dand patta. This huge weapon consists of a long hilt that could cover the holder’s hand till the elbow and a long, flexible blade. Also to be found here is an inscribed sword of the 3rd Shahaji from Tanjavur. There are various hilts known by their make like Karnataki, Mulheri, Purbi, Jodhpuri, Udaipuri, etc. Many of these are beautifully carved with precious stones and styled in damascened, bidri work.

Daggers performed major role in the close-combats. Diverse forms of daggers like Jambiya, Katyar, Khanjar, Peshkabj, Kard etc. decorated with intricate carvings, jade, ivory hilts can be seen here. Other arms include small and big shields made of leather, turtle back and metal. Some are inscribed with Arabic messages. Other remarkable weapons include Jagnol, Gurj, Dao, Kanpatimar and Ankush. Bagh Nakh (Tiger Claws) reminds us the meeting of Chhatrapati Shivaji and Adilshahi general Afjalkhan.

Image 3: Fish-scaled armour

The collection of arms cannot be completed without fire-arms. Cannons, flint-lock and match-lock guns, Percussion cap, long barrel Muskets, Blunder-burst along with revolvers are unique in style. The gun-men used to carry the gun powder to blow these guns in flasks. Kelkar Museum has a remarkable collection of such flasks. Made of different materials like wood, metal, shell these gunpowder flasks are from seventeenth century onwards; and mainly of Rajasthani style. The wooden flasks are tiger-faced while one in the shape of coiled snail has makara-mukh. Among armours, the intertwined chains were famous in medieval period. Fish-scaled, crocodile hide armours and leather jackets are noteworthy. (Fig. 3)

Leather Puppets

A characteristic feature of Indian folk art is leather puppets. Made from leather, these puppets are played with sticks on a white curtain at night. They are made of goat skin and coloured with natural pigments. The puppets are handmade which include the process of cutting, sewing, polishing, mending and colouring. Leather puppetry is prevalent in almost all parts of south and eastern India including Kerala, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Andhra, Maharashtra, Goa and Orissa.

Image 4: Leather puppet

Raja Kelkar Museum possesses a great collection of more than 3000 leather puppets from all parts of India. Based on the mythological stories from Ramayan and Mahabharat, there are sets of 19 stories. They include illustrations of Ram-Sita, Lakshman, Hanuman, Ravan, Lav-Kush, Pandavas and also birds and animals. The Museum has done digitization of these puppets with a conservation point of view. (Fig. 4 & 5)

Image 5: Leather puppet

Another pride variation of this type is 17th and 18th century Paithan ‘Chitrakathi’ paintings. Originally from Paithan near Aurangabad (Maharashtra), they strikingly resemble the leather puppets in themes and style. Along with Ramayan and Mahabharat, they mainly deal with the Hari Vijaya (story of Harischandra), Vetal-Panchavisi (related to magic), Chhalachhandu Akhyana (folklore) etc. The paintings are done on hand-made paper and two paintings are stuck back-to-back. Numbering more than 5000, they demonstrate a rich tradition of this dying folk art and help in understanding the contemporary society, dressing, jewellery, weapons, and village life. (Fig. 6)

Image 6: Paithan Chitrakathi

Objects Belong to Legendary Personalities

The symbolic meaning of artefacts might change with the time or, sometimes more connotations might get added to it. It has happened in the case of the quilt of Dr. Anandibai Joshi. In the second half of 19th century, when women had to handle only hearth and children, Anandibai’s husband Mr. Gopalrao Joshi encouraged her to study further. She completed her matriculation and went to USA to study medicine. Facing all the social restrictions, financial problems, language and cultural barriers, she succeeded in getting the M. D. from Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1886 and became Dr. Anandibai Joshi, the first woman physician of India. But unfortunately, due to harsh weather, lack of essential warm clothing and strict vegetarian diet, she got TB and very soon after returning to India, died a tragic death in 1887 at the age of just 22.

While she was coming back from USA after completing her education, her friends decided to give her a souvenir. So they, including Anandibai and Gopalrao embroidered their names on small pieces of cloth and together stitched in a quilt. Her friends wished that Anandibai will always feel the warmth of her friends’ love close to her through that quilt.

After her death, this quilt passed on to Kaka Kelkar which is now displayed in the textile gallery of the Kelkar Museum silently narrating the saga of a simple middle class lady who, cherished an impossible dream and against all odds, accomplished it. We can read how her own people tried to pull her back, suppress her and how some unknown foreigners, just seeing her courage and efforts helped her by all means. (Fig. 7)

Image 7: Quilt of Dr Anandibai Joshi

A display of Govind Ballal Deval’s belongings gives us similar experience. He was a famous Marathi playwright but new generations hardly know him. Born in 1855, Deval was influenced by then leading playwright-actor Balwant Pandurang Kirloskar alias Annasaheb Kirloskar and joined his ‘Kirloskar Natak Mandali’ around 1875 where he later became a playwright and director.

From 1886 to 1916, Govind Ballal Deval wrote and presented seven famous plays; Durga, Mruchchakatik, Vikramorwashiya, Jhunjarrao, Shapa Sambhram, Sangeet Sharada and Sangeet Sanshaykallol. His plays Mruchchakatik (1889), Vikramorwashiya (1889) and Shapa Sambhram (based on Banabhatta’s “Kadambari”) are good examples of adaptation of Sanskrit plays into Marathi. He introduced the Shakespearean tragedy to Marathi stage by adapting Othello as Jhunjarrao (1890) also Ezabela as Durga (1886). He also wrote lyrics of many songs of his plays and composed their music too. Follower of the reform movement, he criticised the tradition of child marriage through his play Sharada.

Image 8: Objects of Govind Ballal Deval

Bhau Kolhatkar, Nanasaheb Joglekar, Ganpatrao Bodas, Balgandharva were some of his great pupils; who later took the Marathi stage to its golden era. For his creditable play-writing, the maharaja of Gwalior gifted him a long silk coat, ‘uparane’ (a shoulder garment), pagdi and silver handled walking stick in1900 and arranged his procession on an elephant. All these objects displayed in the Kelkar Museum awaken memories of his contribution to the Marathi stage in 19th century. (Fig. 8)

Also, the museum possesses priceless musical instruments of renowned singers and musicians like Bande Ali Khan, Hirabai Badodekar, Pannalal Ghosh, Sawai Gandharv, Balgandharv and Pandit Dattatray Paluskar. The Sarinda used by great writer P. L. Deshpande in his famous film ‘Gulacha Ganpati’ is displayed here. Though inanimate, these objects make alive specific episodes of our cultural history.

Several things are erased with the waves of time. The Kelkar Museum has preserved diverse pages of history through its collection. It displays medieval lifestyle along with certain disappeared words, idioms related to it. ‘Daruche baste’ (gunpowder flasks), ‘ganjifa’ (a card game), ‘sandhyechi pali’ (a ritual spoon), ‘garbi’ (a typical Gujrati tree-shaped lamp) are some examples which now can be seen rarely elsewhere. Every artefact of this museum has a story to tell us. They work as a link between us and our forefathers. Knowing them, studying them thoroughly is the only way to decipher the unknown letters of our history and culture.

Bibliography:

Joshi, Mrudula. 2011. Pursuit and Rhetoric of Dinkar Kelkar: Preserving Heritage of India. Pune: Raja Dinkar Kelkar Museum

Joshi, Mrudula. 2017. Maharashtrache Shilpakar: Sangrahalaya Maharshi Dr. Dinkar Gangadhar kelkar urf Kavi Adnyatvasi. Mumbai: Maharashtra Rajya Sahitya Ani Sanskruti Mandal

Anand, Mulk Raj (Ed). 1978. Treasures of Everyday Art: Raja Dinkar Kelkar Museum. Vol XXXI, No. 3. Bombay: Marg Publications.

Pearce, Susan. 1992. Museums, Objects and Collections: A Cultural Study. Leicester and London: Leicester University Press

Wagh Pratibha.(Ed.) 2010. Leather Puppets. Pune: Raja Dinkar Kelkar Museum

2006. Chitrakathi: Folk Painting of Paithan. Pune: Raja Dinkar Kelkar Museum.